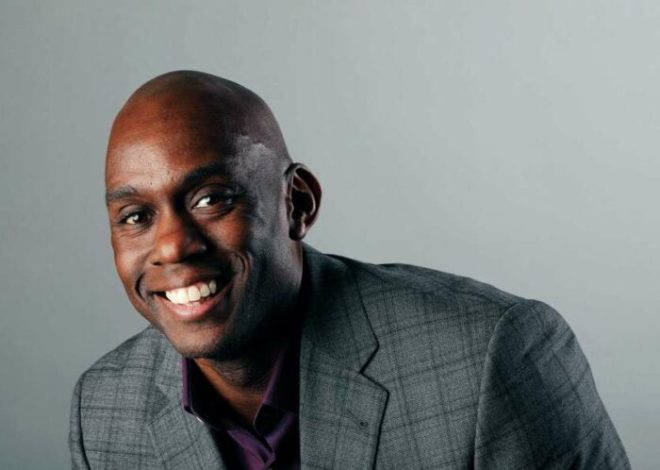

The US jazz icon with a controversial legacy

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWith the release of new, previously unheard live recordings from the BBC, questions remain over Louis Armstrong’s complicated and controversial career and persona.

More than half a century after the death of Louis Armstrong, fans and critics are still arguing over his name. Is it pronounced Lewis or Louie?

In some ways, this duality is appropriate, reflecting the ambiguities in Armstrong’s character and persona. The journalist Murray Kempton famously summed him up as a combination of “the pure and the cheap, clown and creator, god and buffoon”.

Warning: This article contains language that some may find offensive.

This month, with the release of a new album of live recordings, fresh material has been added to the ongoing debates about Armstrong’s contradictions. Titled Louis in London, the record showcases both Armstrong’s jazz genius and vaudevillian silliness. It also hints at the more contentious complexities of Armstrong’s attitude to racism.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe newly released recordings were made at the BBC in London, during Armstrong’s 1968 UK tour. This period marked his peak popularity, coming just weeks after What a Wonderful World topped the UK charts. But it was also the end of his career. After the tour finished, Armstrong was struck by heart and kidney issues, from which he would never fully recover.

Retreating to his New York home, an ill Armstrong began cataloguing his lifetime of recordings. He became particularly enamoured with the BBC recordings, playing them to visiting friends, making copies for his bandmates, and attaching a label to his personal copy that seemed to signal his intentions: “for the fans”.

Despite Armstrong’s love for these performances, they were only given a partial release after their initial broadcast. The album released this month presents a much fuller version of the BBC recordings, adding five new songs to those already issued. It also includes an alternative take of Hello, Dolly! which is “different, longer, and better” than the previous version, according to Ricky Riccardi, director of research collections at the Louis Armstrong House Museum.

Riccardi, who helped assemble the album, has some theories about why the BBC performances were so important to Armstrong. “It’s all about context,” Riccardi tells the BBC. “Shortly after the UK tour, his body finally gave out. So, I think there was a part of him that was coming to terms with the fact that he might never again perform onstage for his fans.”

In this way, Armstrong may have seen the BBC shows as his final great performances – a “last hurrah”, as Riccardi puts it. “Even before his more serious health issues, the live concerts could be a bit erratic,” Riccardi says, referring to the lip and dental problems that affected Armstrong’s trumpet-playing as he got older. “But the London shows demonstrate that he was still capable of providing spine-tingling moments with his horn at such a late stage in life.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn addition to the quality of his playing, Armstrong may have felt the BBC recordings were special for another reason. They seemed to sum up his entire career – with the setlist spanning every decade of his performing life.

First, there is Ole Miss, a jazz instrumental that Armstrong started playing as a teenager in the 1910s. Then there is Rockin’ Chair, a novelty song that Armstrong first recorded in 1929. Further tracks trace the remaining decades: When It’s Sleepy Time Down South was first recorded in 1931, Blueberry Hill in 1949, and Mack the Knife in 1955. The set is completed with Armstrong’s 1960s hits, including his signature song What a Wonderful World.

Pioneer or popular entertainer?

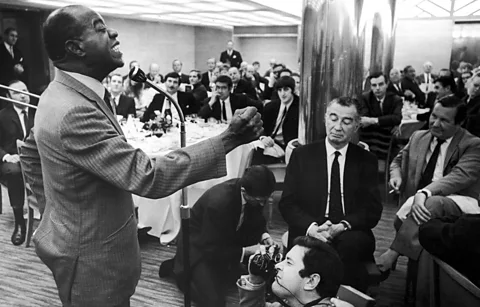

But as well as providing a decade-by-decade summary of Armstrong’s career, the Louis in Londonalbum also captures his complex identity as a performer.

During the UK tour, several critics remarked on the tension between Armstrong’s status as a jazz pioneer and his proclivity for crowd-pleasing antics. A reviewer for Melody Maker observed: “The emphasis is heavily on singing and clowning, and lovers of the Louis trumpet may be disappointed.” A critic for The Times concurred: “As a show business performance, it was superb. From a jazz point of view it was quite undistinguished.”

The BBC setlist seemed to reflect this. It included some jazz instrumentals, but leaned more towards commercial fare, such as a rendition of The Bare Necessities from Disney’s The Jungle Book.

Riccardi argues that this had long been a feature of Armstrong’s performances. “It’s a false narrative to say that Armstrong was an artist in the 1920s but then ‘sold out’ and wasted all that promise,” he says. “Everything he was criticised for doing later in his career, he was already doing in the 1920s and 1930s – performing pop songs, playing Broadway showtunes, and doing broad comedy.”

Jazz critic and author Jordannah Elizabeth suggests that the criticisms of Armstrong’s showmanship emerged as he transitioned on to the global stage. “He was subject to an intellectualisation of jazz by some critics, who imposed strict parameters around what they believed constituted ‘high art’,” she tells the BBC. “This derived from a Eurocentric resistance to physical freedom onstage – movements of the hips, big smiles on faces.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHowever, Elizabeth acknowledges that Armstrong’s stage persona was more complex, and harked back to a US tradition of minstrelsy. “Some of Armstrong’s performance elements were seen as similar to the characterised performances of white actors in minstrel shows, which were active from the 1800s through 1910, a little after he was born in 1901. The tradition stuck around in America in less widely accessible circles, but it was still prevalent until the 1960s, and pandered to certain stereotypes,” she says. “Also,” she adds, “most of his career came before the civil rights movement, so he likely experienced a lot of pressure to project and uphold his original persona.”

This more controversial aspect of Armstrong’s performances is reflected in the BBC setlist, which opens with When It’s Sleepy Time Down South. Although it was popular with audiences, the song had courted controversy for offering an idealised vision of the American South and using the racial epithet “darkies”. In the 1950s, as the civil rights movement was taking hold in the US, protestors even burned copies of the song.

By the time of the BBC recordings, Armstrong had substituted the offending term for the more neutral “folks”. But his persistence in keeping the song as a show opener, coupled with his grinning onstage persona, attracted criticism from his peers. Fellow trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie accused him of “Uncle Tom-like subservience”. Miles Davis felt that “his personality was developed by white people wanting black people to entertain by smiling and jumping around.”

Elizabeth offers some defence of Armstrong. “During the difficult times of the civil rights movement, Americans needed someone to give them an escape, a smile to remember, and a comfort zone,” she says. “Armstrong assumed that role, which naturally brought a bit of disdain and backlash from the jazz artists on the front lines of the movement.”

Riccardi adds that Armstrong made his own contributions to the civil rights cause outside of the spotlight. “He donated heavily to Martin Luther King,” Riccardi says. “When New Orleans passed a law prohibiting integrated bands from performing in public, Armstrong refused to go back for almost a decade. He was also one of the first African-American entertainers to have it in his contract that he would not play a hotel unless he could stay there.”

Armstrong pushed some advocacy into the music too, making it part of a palatable package of entertainment. On the BBC recordings, he dedicates You’ll Never Walk Alone to “all the mothers who have sons in Vietnam”. He had previously performed this song for segregated black audiences in the US as a show of solidarity. Armstrong described one performance in Georgia as the “[most] touching damn thing I ever saw” when the audience began to sing along. “I almost starting crying right there on stage. We really hit something inside each person”.

A complicated legacy?

But perhaps the best representation of his philosophy is What a Wonderful World, which serves as the penultimate track on Louis in London. Some critics dismissed the simplicity of the song’s message at the time – the New York Times called it “sentimental claptrap”. But Armstrong explained himself in a spoken-word introduction added to the song a few years later: “Seems to me, it ain’t the world that’s so bad, but what we’re doing to it. And all I’m saying is, see what a wonderful world it would be if only we’d give it a chance.”

This attitude eventually won over some critics. “I misjudged him,” Dizzy Gillespie admitted after Armstrong’s death. “I began to recognise what I had considered [Armstrong’s] grinning in the face of racism as his absolute refusal to let anything, even anger about racism, steal the joy from his life and erase his fantastic smile.”

Others remained ambivalent. Even after Armstrong had passed away, Miles Davis repeated his criticisms. “I hated the way he had to grin in order to get over with some tired white folks,” he wrote in his autobiography. But still, Davis had to acknowledge that Armstrong had “opened up a whole lot of doors for people like me to go through”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDespite the controversies, Elizabeth believes that Armstrong’s legacy is secure. “None of the criticisms keep him from maintaining his place in jazz history,” she says. “He was greatly loved and respected and remains so to this day.”

Listening to Louis in London now, more than 55 years after it was recorded, one can hear both sides of the story. On some songs, Armstrong the legendary jazz trumpeter emerges. On others, he assumes his role as a popular entertainer. Likewise, with a track listing that spans 50 years of US history, one can recognise Armstrong’s status as a pioneer who broke down countless barriers. But one can also observe his tendency to stray into territories that might be considered racially regressive, both now and then.

So, while Louis in London offers fans a chance to hear Armstrong one last time – at his final peak – it cannot offer any definitive conclusions on the complexities of his character and persona. They may even be symbolised by the album’s sequencing, which places the songs Hello, Dolly! and Mame one after the other. On both tracks Armstrong sings his own name. But on one song he calls himself Lewis, and on the other Louie. And so, the debate continues.

Louis In London, released by Verve Records on 12 July, is available on vinyl, CD and digital.