With a ‘Ring,’ the Dallas Symphony Becomes a Wagner Destination

Richard Wagner conceived his four-opera “Ring” as a Gesamtkunstwerk: a marriage of poetry and music, for voices and orchestra, with coordinated sets, costumes and action. It’s a huge, expensive challenge even for top opera companies, calling for powerful singers, an accomplished conductor and orchestra, and a stage director and designer who can enliven a convoluted epic of family dysfunction, greed, destruction and rebirth.

How much of Wagner’s impact remains if you subtract scenery and costumes, and most of the action — with neither water nor fire, sword nor spear, celestial palace nor subterranean smithy?

Those questions will be put to the test by the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, which is alone in the American classical music and opera scene this season by presenting a complete “Ring,” over four evenings at the Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center beginning on Sunday.

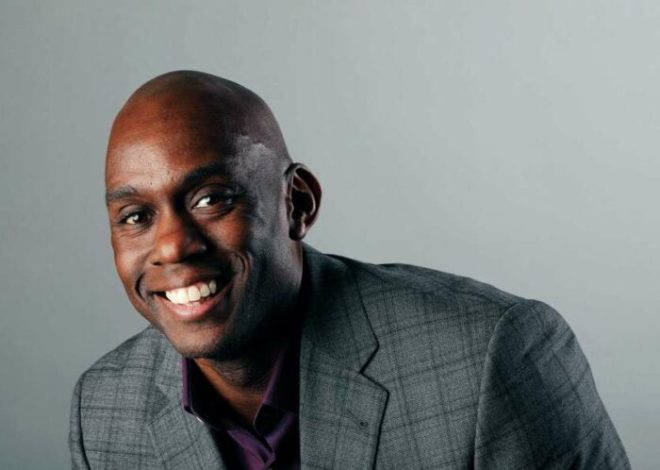

At the podium will be Fabio Luisi, the orchestra’s music director since 2020, who led the “Ring” at the Metropolitan Opera a dozen years ago. In Dallas, he began to roll out the cycle last spring, presenting “Das Rheingold” and “Die Walküre”; “Siegfried” and “Götterdämmerung” followed earlier this month, semi-staged by Alberto Triola, who collaborated with Luisi and the Dallas symphony on “Salome” and “Eugene Onegin.”

A concert staging of the “Ring,” Luisi said in a video interview from his home near Zurich, does not compromise the work.

“In Wagner’s time the acting was extremely reduced,” he said. “We cannot compare the acting in the ’60s and ’70s of the 19th century with acting now. Even after the war, in Bayreuth, the stagings by Wieland Wagner were pretty much static.”

And by shedding the operas’ visual elements, “we can focus more closely on the music,” Luisi said. “It is a beautiful idea that the music can inspire our audience to imagine, to use their fantasy. If you listen to an opera on record, it’s pretty much the same.”

That music is, after all, vivid — and was revolutionary in its time. Wagner rejected older recitative-and-aria conventions; used leitmotifs to identify characters, objects and hidden thoughts; wrote elusive, fluid harmonies; and orchestrated with new instrumental colors.

Costuming and staging the “Ring” requires a lot of time, beyond rehearsals. But concert performances, while considerably less expensive, are still challenging.

“We had very limited resources in terms of time, in terms of possibilities technical and logistical,” Triola said. “We do not have enough space to do something theatrical. I was forced to imagine another option.”

Triola opted for minimal interactions among the cast members, as well as lighting colors coded to some individuals and settings — light motifs, if you will.

“I don’t want in any case to ask the singers to lie down,” he said. “When Fasolt is killed by his brother, the light simply goes off. Brünnhilde, instead of staying onstage until the very end and lying down with fire all around, will leave the stage when Wotan starts his marvelous farewell. It’s a very symbolic acceptance, and she will appear again in the symbolic area of the organ above the stage. The fire will be projected on the organ.”

At “Das Rheingold” and “Die Walküre” in May, with singers at the front of the stage and the orchestra behind on risers, the sonic impact was often hair-raising, even if the dramatic and vocal results were uneven.

Stefan Margita and Michael Laurenz vividly characterized Loge and Mime. But while Tomas Tomasson’s Alberich looked aptly sinister and sang powerfully, he was dramatically inert. Inscrutably, even when singing of their love, Sara Jakubiak’s Sieglinde and Christopher Ventris’s Siegmund were isolated on opposite sides of the stage. Mark Delavan had the rich porridge of a baritone for Wotan, but not the oomph. Lise Lindstrom’s Brünnhilde had a potent, steely top, but too little substance in lower-range writing.

Margita, who also sang under Luisi in the Met’s “Ring,” said that he conducted with skill and sensitivity.

“He has a very calm and professional manner with the singers,” Margita said in an email. “He is incredibly flexible to make sure he meets their most important needs. Fabio brings to the whole ‘Ring’ exactly what Wagner wanted, amazing energy and certainly precision in beautiful music.”

Luisi was initially trained as a pianist in his native Genoa, Italy, and became interested in conducting during a stint of accompanying singers. He studied conducting in Graz, Austria, where he began working with the local opera and symphony orchestra. He went on to sometimes overlapping principal conductor positions with the Tonkünstler Orchestra and Vienna Symphony in Austria, the MDR Symphony Orchestra and the Semperoper in Germany, the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande and the Zurich Opera in Switzerland, and the Danish National Symphony Orchestra.

Luisi became the Met’s principal guest conductor in 2010, and was named principal conductor the following September, when James Levine, the house’s long-reigning music director, was sidelined by health issues. Luisi took over numerous productions, including Robert Lepage’s new, divisive “Ring.” When the Met released a Grammy Award-winning set of DVDs of that staging, it was with Levine conducting the “Rheingold” and “Walküre,” and Luisi the “Siegfried” and “Götterdämmerung.”

It was widely speculated that Luisi was Levine’s heir apparent, but Luisi said that there was never any official discussion of his becoming music director, and he stepped down when Levine returned for the 2016-17 season. (Levine, who died in 2021, was fired in 2018 over allegations of sexual abuse and harassment, which he denied.)

Including guest conducting, Luisi’s career has varied in its balance of opera and symphonic performances. In the last three years, he said his schedule has been 90 percent symphonic, 10 percent opera. This project in Dallas is both, in ways that can be difficult for players and audience members alike.

A typical orchestra concert runs about two hours, including an intermission; “Götterdämmerung,” on the other hand, has two intermissions and pushes six hours. The challenges are mental as well as physical, and the Dallas Symphony’s management worked with the players’ committee to develop reasonable rehearsal and performance schedules.

“My biggest challenge is going to be endurance and focus,” said Daniel Hawkins, the orchestra’s principal horn. “This is close to 15 hours of music.”

There will be about 10 horn players in rotation throughout the cycle; almost none of them have played an entire “Ring,” Hawkins said. “There are also different instruments,” he added. “Four of the players will have to put down their French horns and play Wagner tubas. A trombone player will have to play bass trumpet.”

Neither Opera America nor the League of American Orchestras could think of another American symphony orchestra attempting a full “Ring.” But Luisi believes it’s an important experience for orchestra musicians, cultivating new degrees of attention and responsiveness.

“After I conducted the last bar of ‘Götterdämmerung’ the first time, my life changed,” he said. “My life as a musician changed. My perception of time in music changed. If only one musician in my orchestra could have an experience like that, I would be the happiest musician in the world.”